I watch a lot of horror movies. However many you’re thinking right now, I regret to inform you that you have woefully underestimated the number of horror movies that I have watched in my lifetime. I watch a lot of horror movies. My earliest cinematic memories involve horror movies—Alien when I was three years old, sitting on my uncle’s lap in the living room of our old apartment; The Blob after a midnight trip to the emergency vet to have a cattail removed from my cat’s eye; Critters in my grandmother’s living room, elbows buried in the plush beige carpet, dreaming of marrying the handsome red-haired boy in the lead role. So many horror movies. The only form of media that has arguably had more of an influence on me than the horror movie is the superhero comic book (which is a whole different kettle of worms).

The standards of horror have changed with time, of course. The things we’re afraid of now and the things we were afraid of fifty years ago are not the same, and neither are the avatars we choose to face those fears. We’ve gone from jut-jawed heroes to final girls to clever kids to slackers who somehow stumbled into the wrong movie, and when it’s been successful, it’s been incredible, and when it’s failed, we haven’t even needed to talk about it, because everyone knows. But there’s one ingredient to a really good horror movie that has never changed—that I don’t think ever will change—that I think we need to think about a little harder.

Sincerity.

There’s a point in Creepshow II where a beautiful girl has been grabbed by the oilslick monster that lives on the surface of an abandoned lake. It is eating her alive. She’s awake, aware, and screaming. Her friends are freaking out, because that’s the reasonable thing to do under the circumstances. But none of them are refusing to commit to the moment. The monster is there. The fact that the monster looks like an evil pudding doesn’t change the fact that the monster is there.

There’s a moment in Slither where the mayor of the small town under siege by alien invaders loses his temper because there’s not a Mr. Pibb in his official mayoral car. He has seen people die. His own life has been threatened. He may not last until morning. He just wants his Mr. Pibb. It’s one of the most fully committed, most human moments I have ever seen in a horror movie, and it did more to sell me on the terror of the situation than all the overblown confessions of love in all the sequels in the world.

Sincerity. Completely committing to the situation, no matter how silly. Whether chased by giant snakes (Anaconda), or super-intelligent sharks (Deep Blue Sea), or a flesh-eating virus (Cabin Fever), or even Death Itself (Final Destination), sincerity can be the difference between a forgettable Saturday night special and something that you’ll find yourself going back to. “So bad it’s good” is a phrase most often applied to horror movies with the sense to be sincere.

I find this is true of most mediums. The Care Bear Movie holds up surprising well, because it had the guts to completely commit to its source material; so does the original V. Some newer material falls apart on re-watching because it never figured out how to be sincere. Fully committing to the topic at hand, on the other hand, gives you something worth revisiting a time or twelve.

We scare because we care, after all. Caring counts.

This article originally appeared in the Tor/Forge newsletter in April 2016. Join the mailing list here.

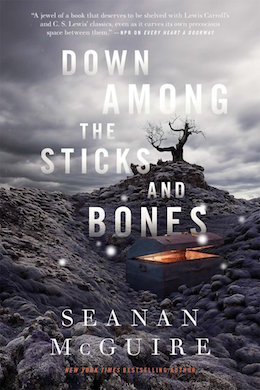

Seanan McGuire is the author of the October Daye urban fantasy series, the InCryptid series, and several other works, both standalone and in trilogies. She lives in a creaky old farmhouse in Northern California, and was the winner of the 2010 John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer. In 2013 she became the first person ever to appear five times on the same Hugo ballot. Her novella Every Heart a Doorway is available from Tor.com Publishing; its companion, Down Among the Sticks and Bones, publishes in June 2017.

Seanan McGuire is the author of the October Daye urban fantasy series, the InCryptid series, and several other works, both standalone and in trilogies. She lives in a creaky old farmhouse in Northern California, and was the winner of the 2010 John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer. In 2013 she became the first person ever to appear five times on the same Hugo ballot. Her novella Every Heart a Doorway is available from Tor.com Publishing; its companion, Down Among the Sticks and Bones, publishes in June 2017.